How The Drowning Rats Experiments Started

Dr Curt Paul Richter is a well known American Psychobiologist and geneticist who conducted research in the areas of behavioral physiology.

Before Curt P. Richter started his famous “Drowning Rats Psychology Experiments”, there was a paper published by Walter Cannon in 1942, entitled “Voodoo Death”. Cannon documented reports of sudden deaths of people under the influence of voodoo from around the world and how they died.

In the paper, Cannon theorised that people under voodoo spells (or boned) died suddenly as they enter a state of shock due to an overdose of adrenaline produced by their bodies as they believed that evil spirits are able to cause harm to their lives.

He started experimenting on the anger and fear in cats and concluded that both fear and anger can have serious negative effects on our health when these 2 emotions have a prolonged presence.

This research probably contributed to Walter Cannon inventing the phrase, “fight-or-flight response”.

He suggested that other researchers should observe the respiratory system, pulse rates, and concentration of the blood of people under voodoo spells to test his theory.

Why Did Curt Richter Drown The Rats

Richter, in hope of testing Cannon’s theory on sudden unexplained deaths in man, designed a series of experiments to drown rats as he varied the conditions in the environment, to measure their survival times. Fortunately for him, he didn’t get into trouble with the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Jokes aside, this experiment, cruel as it may seem, became a well-known research that gives some very meaningful insights into motivation and resilience.

Setup Of The Drowning Rats Experiments

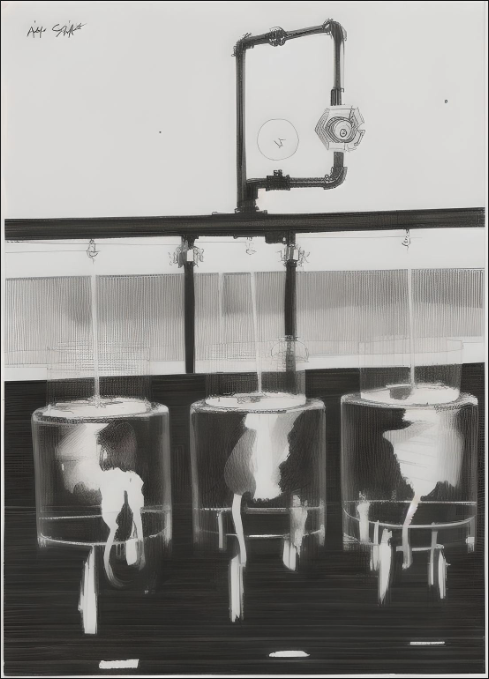

Figure 1: Sketch of how the glass jars were set up with the rats inside, together with faucets, jets of hot and cold water, pressure gauges and pressure regulator.

The researchers observed that the survival times increased as the water temperature rises, from 17.2℃ (63℉), peaks at 35℃(95℉) and decreases as the temperature continues to rise.

On the average, the rats can survive 50-60 hours treading water in the jar, at water temperatures of 32.2℃ to 37.8℃ (90℉/ to 100℉/). The longest average survival time was 60hrs at 35℃ (95℉).

Rats Without Whiskers

Richter noted that there were some outliers in his initial experiments, where, at every temperature, some rats would either drown within 5-10 minutes or swam for as long as 81 hours.

He then recalls another research, by Dr Gordon Kennedy. In 1953, Kennedy was researching the metabolism of rats by feeding them salt and measuring the amount of sodium excreted in their urine.

The rats would unknowingly contaminate their urine with the salt trapped on their whiskers and facial hair. To solve this problem, they snipped off the facial hairs of the rats.

Kennedy then noticed that one of the three rats started poking its snout into corners of the cage and into the food-cup in a cork-screw motion and it died within 8 hours of this abnormal behaviour.

Richter got the idea that there might be some effects if he trimmed the whiskers of the rats before immersing them in the water jars.

They started experimenting with 12 domesticated rats with their facial hairs trimmed before immersing them into the water at 35℃ (95℉), their “favourite” water temperature.

The first 3 domesticated rats swam around the brim, dove to the bottom with their noses touching the glass walls and died within 2 minutes, without resurfacing to breathe at all. This came as a surprise to the researchers as they were expected to swim for 60-80 hrs in the 35℃ water (95℉). The other 9 swam 40-60 hrs.

They then repeated the experiment with 6 rats that are crossbred from wild rats and domesticated rats. 5 out of 6 hybrid rats died in a very short time.

Finally, Richter and his team put 34 rats through the same test. The outcome was an unexpected one. Wild rats are exceptionally fierce, aggressive and known to be stronger and fitter than domesticated rats, yet all 34 wild rats died within 1 to 15 minutes of immersion into the water jars.

Large Scale Testing

Richter and his team repeated the experiment on more than 2,000 wild rats after fine tuning the process of removing them from the cage, covering them with a cloth funnel, trimming their facial hairs and inserting them into the water jars.

They initially observed that trimming the whiskers destroyed their most important means of contact with the outside world, especially to wild rats, causing their deaths.

Observations And Further Testing

However, they realised that there were other factors that could be stressful to the rats, he listed 10 of them in the paper, like being trapped in the cage, being handled, held in an upright position… etc. Of these, they concluded that 2 of them – the fact that they were being inhibited physically and the immediate threat of getting drowned, had the greatest impact on the wild rats.

Some wild rats died when they were being handled, before their whiskers were trimmed, others died when they were dropped directly into the water, without being handled. In fact a majority of the rats died because of these 2 factors.

They concluded that the trimming of the facial hairs of the rats contributed lesser to the deaths compared to these.

Eager to find out if Cannon’s fight-or-flight theory applied to the rats, Richter measured the heart rates, body temperature and also performed autopsies on the rats to determine if they died from overstimulation of the body or secretion of body chemicals. They concluded that the rats died from overstimulation as their hearts were bloated with blood.

Injecting the rats with cholinergic drugs (to calm them down) didn’t increase their survival rates significantly.

He then theorised that the quick deaths were caused by a sense of hopelessness. To test this out, they began holding the wild rats briefly, then releasing them, letting them swim for a few minutes on several occasions, then saving them.

By exposing them to the stressful conditions gradually and making it go away, the wild rats were convinced that the situations were not hopeless and were able to consistently clock longer endurance timings that are consistent with the domesticated rats.

Richter concluded that the “boned” victim, like the rats, didn’t die of a fight-or-flight response, but rather a sense of hopelessness, resigned to his fate.

How Does Curt Richter’s Experiments Apply To Our Workplace?

- Always Think Positively

Our beliefs play an important role in our survival. If we believe voodooism and a voodoo casts a spell on us, we may lose hope and die.

- Know Your Strengths

Regarding the outliers that Richter mentioned(those that die prematurely), I believe there is a chance that the individual rats just find a particular situation extremely stressful – whether it be being handled or being thrown into water at a particular temperature, or having their facial hairs trimmed, and that would have contributed to their state of stress, causing them to give up hope. Consider our DISC workshop to learn more about your personality trait.

- Choose The Right People

Putting the right person to do the right task or training can help improve performance. Similarly, knowing our strengths and areas of improvement can help us choose the right battles to fight.

- Set Realistic And Achievable Goals

Different people have different strengths, just like some rats are exceptional swimmers and can tread water for 81 hours while others die within 2 minutes. Few people thrive when they are given an unachievable goal. Setting realistic goals with gradual training and conditioning over a period of time will help us achieve our goals.

- Stay Hopeful

Choose to believe that the difficult situation will improve. Pray to God. Go to church. Believe that Jesus loves you. Do whatever it takes to give you a confident expectation of good in your life. In this way you will continue to do what is necessary to help you survive.

If you like this article, you may also like our Corporate Training & Leadership Team Building programmes.

Source:

Research paper published in 1957 “On the Phenomenon of Sudden Death in Animals and Man”

https://www.aipro.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/phenomena_sudden_death.pdf

Figure 1 courtesy of fotor.com

https://www.fotor.com/features/photo-to-sketch/